A Talk With Chef Jordan Kahn About the Multi-Course Architecture of Vespertine

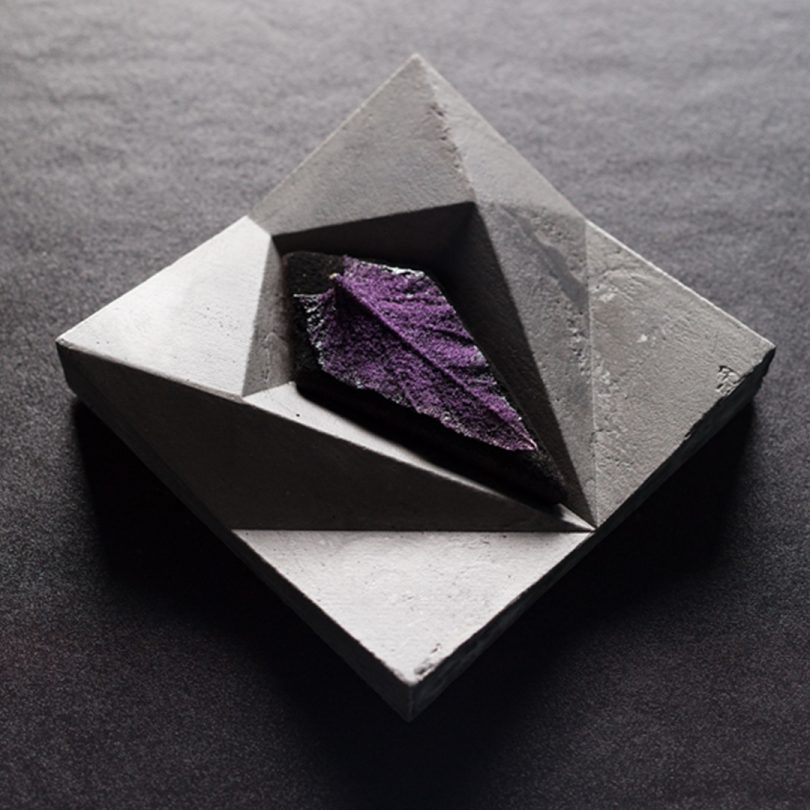

There are few restaurants in the world as honored for its architecture as its menu as Los Angeles’s Vespertine. Designed by lauded architect Eric Owen Moss, first impressions of Vespertine’s umber steel structure often evoke pronouncements of a wildly conceptual structure – an “insane architectonic utopia“, a design garnering numerous architecture, interior and industry awards since its unveiling in 2017. But upon closer and studied inspection, the design in its entirety reveals a highly controlled and conceived space that has evolved to operate as the spatial accomplice to its culinary counterpart as conjured by Chef Jordan Kahn. There is a method to its madness. And embracing the abstractions entrusted by its architect, Chef Kahn has adopted Moss’s work as a physical totem to his own spirited work within the kitchen.

Located in an industrial corner of Culver City’s Hayden Tract, Vespertine’s sculptural imprint began with a pre-existing structure of Moss’s design locally and affectionately known as the Waffle – a vertical pronouncement upon the urban landscape that seems to have almost wiggled from underneath. Within its curvaceous grid-clad exterior, Vespertine operates as a multi-stage dining experience where Kahn’s guests are guided into, upward and out from the Waffle into an outdoor garden, perhaps an abstraction of the act of eating itself. The late great Jonathan Gold once described the dining experience awaiting within as “mandatory in the way that the James Turrell show at LACMA was mandatory” and otherworldly with his pronouncement, “you may as well be on Jupiter.”

Now several years in operation since its opening, Vespertine has settled into something rare and special for any architectural project, but even more notably so for any restaurant and its architecture: a landmark. We spoke with Chef Jordan Kahn to ask about his collaboration with architect Eric Owen Moss, and discuss how Vespertine’s architecture has influenced his perspective of the fine dining experience.

How did the partnership between yourself and Eric Owen Moss come about?

My relationship with Moss began before I met him. I discovered a new building he designed titled, “Waffle”. The building was about 60% complete when I first encountered it, but it struck a chord with me in a way that I had never felt before. From that point forward, I became obsessed with the structure. I knew nothing about Eric Owen Moss, Frederick and Laurie Smith, Hayden Tract, nor avant grade architecture frankly. Yet, I returned almost every night to wander the grounds and stare at the structure, transfixed in its form and movement.

I used to bring a screw driver with me so I could break in to the construction site without anyone knowing, wandering inside the building for hours, wondering what this was exactly. After several months of these clandestine visits, an idea began to take a very loose form. I was able to develop enough of an idea to meet Moss and discuss my vision with him. My first meeting with [Moss] was intriguing. Our conversation was illuminating and harmonious, yet cumbersome in some ways, as neither of us had the vocabulary to discuss the other’s work accurately. Referencing Ferran Adria and Antoni Gaudí proved to be very helpful.

I’ve read that Eric Owen Moss designed the restaurant independent of any reference to food. But there is an emphasis on the experiential and sensory “flow” of guests upon entry. What was the impetus for taking such an approach to the restaurant’s design versus one where an integration/connection with food/ dining is evident?

The building was originally designed as a conference center. When I discovered it, I described the concept to Moss and we began working together to transform it into a functional restaurant. When we talk about restaurant design however, we first must agree on what a restaurant is: a restaurant is just a vessel, a medium. We design integral experiences that go beyond the form or technique, and through which people generate intimate bonds with their surroundings. There is no beginning, no middle and no end. Our spaces are not meant to be used, but felt.

We design integral experiences that go beyond the form or technique, and through which people generate intimate bonds with their surroundings. There is no beginning, no middle and no end. Our spaces are not meant to be used, but felt.

What hand did you play in the design and/or specifications of the design?

The core structure and facade was built before I came. Those are Eric’s designs. I began with the journey of the guest. Once this was developed, Eric and I had a map, and we began collaborating on everything from furniture to trays, vessels, garden, water crater and nearly everything a guest touches during the experience.

In hindsight, has the architecture itself influenced your perception of your own cooking methodology and also your approach to the dining experience that wasn’t at first evident?

Vespertine was not an idea I had written down in a notebook somewhere or hidden in a computer file, waiting to discover the perfect vessel. The project was born from the structure and therefore has influence over everything: cuisine, music, language, service, hospitality, experience.

Everything a guest experiences at Vespertine is connected. These are not disparate mediums working in concert, rather it is all one single, cohesive form. As you lay in the center of a forest, you notice the sound of the trees, the chirping of the birds, the flow of the stream, the hum of the bees. They can all be observed as separate, yet are part of the entire ecosystem, inextricably linked.

What is Vespertine like to inhabit while empty of diners?

Typically, a restaurant feels better when it is full of patrons because of the amount of energy generated in the environment. It is observable. Conversely, when a restaurant is empty, oftentimes it can make people feel disconnected and lonely. The energy is absent. Vespertine is simply another form of an organism. It has its own energy. When it is full, the energy doesn’t expand and when it is empty, it doesn’t contract. To answer the questions simply: it is beautiful.

What do you see in regards to the future of dining at Vespertine, post-COVID?

My hope for the future is for people to find a deeper connection and meaning through food. Eating is our most sacred, ancestral, intimate, and vital ritual.

Photos by Tom Bonner Photography.

from Design MilkInterior Design – Design Milk https://ift.tt/3b1I9Eb

via Design Milk

No comments